The ‘Tyburn Tree’

During the 16th century, witchcraft became a popular and much feared explanation for sudden or unexplained misfortune. Failing crops, the death and illness of people and livestock, were all thought to be the work of the devil rather than ‘God’s Will’.

Women were particularly vulnerable to these accusations, in part because they had often been the ones to have roles as healers and midwives, who were particularly singled out because of the belief that they had the power to prevent conception and terminate pregnancy, and also because of the view that women were weak with poor intellect and at the mercy of their lustful thoughts and bodies.

‘The Malleus Maleficarum’ was published in the 15th Century and was a handbook of how to root out and deal with witches. It benefited from the rise in printing presses, making it more widely available than the usual hand written pamphlets. Although it was never adopted by the notorious Spanish Inquisition, it was used by secular courts. It concluded that women were more prone to ‘superstitious’ behaviour than men because they were inclined to be ‘credulous’. They were also more naturally prone to ‘leaking’ and had a ‘lewd and slippery’ tongue.

England never experienced witch trials on the scale that continental Europe did and formal accusations against witches (usually poor, elderly women) reached a peak in the late 16th century and in particular, in South East England.

The East End of London produced two very different cases, one from 1652 and the other in 1944. These are their stories.

The Witch of Wapping

Joan Peterson, ‘The Witch of Wapping’ Pamphlet

Thomas Crompton was a man with a problem. He had managed to charm his way into the affections of the much older and very wealthy Lady Powell, spiriting her away from her family and hiding her in his house in Chelsea. He had gained control of Lady Powell’s estates and finances and was set to inherit a great deal of her riches when she died. Lady Powell’s family intervened and she was reconciled with her husband shortly before her death, leaving her estates and money to her niece, Anne Levingstone, who had cared for her.

But Thomas Crompton wasn’t about to give up. He had already availed himself of Lady Powell’s money and knew there was more to be had. Anne Levingstone needed to be discredited and Crompton thought he had the perfect way of doing it. Joan Peterson of Shadwell was known for her headache cures, potions and charms and had helped local people to recover missing goods and cure sick people and animals. Crompton and his associates approached Joan and tried to bribe her with £100 to say that Anne Levingstone had purchased ‘certain powders and seeds, to help her in her lawsuits, and to provoke unlawful love’

But Peterson wouldn’t be drawn into the conspiracy and more dangerously, now knew too much about Crompton and his plans. Crompton was well connected and could count on Sir John Danvers, an English parliamentarian and co-signer of the death warrant of Charles I, as an ally. Danvers had also married a wealthy older woman and had managed to squander the large sums he had inherited upon her death. They found a local JP who was willing to grant a warrant to search Peterson’s home for ‘Images of Clay, Hair & Nails.’ None were found but Peterson was sent before the magistrate for questioning. She was adamant that she had never met Lady Powell, nor used witchcraft against her. Fatally, she did reveal that ‘Crompton’s woman’ had been to see her and asked her to swear against Anne Levingstone. Peterson was searched for ‘witches’ marks’ but again, nothing incriminating was found and she was released on bail.

Crompton was desperate and Peterson was again questioned and reassured that it was not her they were after, but Anne Levingstone. Joan Peterson held fast and told the truth. She had not seen Anne Levingstone for ‘over a year’ and had nothing incriminating to tell them. Something had to be done to crack Peterson. She was proving to be far too honest and courageous for Compton’s liking. Joan Peterson was examined in a most ‘unnatural and barbarous manner’ and this time a ‘teat of flesh in her secret parts, more than other women had’ was found. This was enough for Joan to be sent to Newgate Prison.

Entrance of Newgate Prison

On the 7th April her trial was held at the Old Bailey. Evidence was heard from those willing to incriminate Peterson (including her own maid and her seven-year-old son) while anyone trying to defend Peterson’s good character were prevented from even entering the building. To make sure of Peterson’s conviction, a second charge was applied. When Christopher Wilson became ill, he sought out Peterson’s help and agreed to pay her a fee for her services. Wilson reneged on the deal and Peterson was known to have loudly cursed him. When Wilson fell ill again, Peterson was thought to be the cause of Wilson’s relapse. Although he never accused her or gave evidence, this was used as a way to secure Peterson’s conviction.

The jury must have been persuaded by the evidence given by Lady Powell’s doctors, that they were impressed that she had made it to eighty, considering she was suffering from ‘the Dropsie, the Scurvey, and the yellow Jaundies.’ Joan Peterson was acquitted of the murder of Lady Powell but was found guilty of bewitching Christopher Wilson. She was executed by hanging at Tyburn on 12th April 1652. Although it is usually assumed that witches were burnt, in England the most common punishment was hanging.

Even at the time, there were suspicions that the trial had been rigged and that Peterson was innocent. Anne Levingstone would bring a court case against Thomas Crompton and the battle for Lady Powell’s estate would continue to rage for a decade.

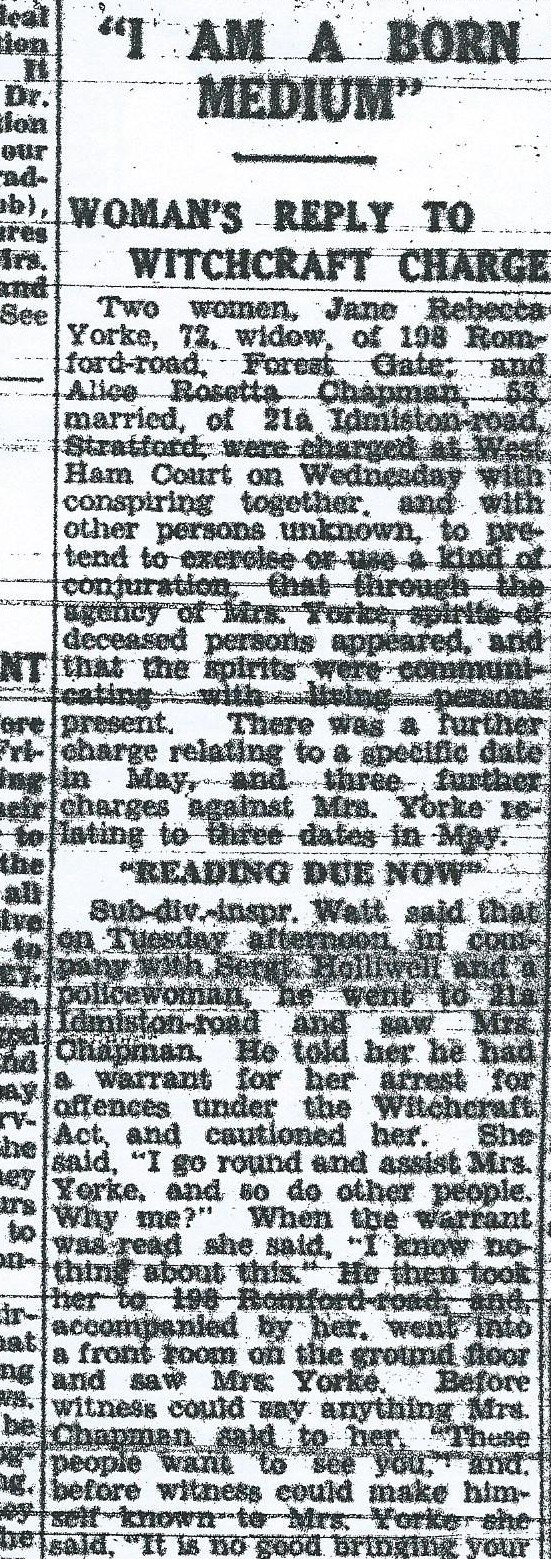

Article about Rebecca Jane York, Stratford Express (14th July 1944)

The Newham Medium

Moving on about 300 years later and in May 1944, the Second World War was nearing its end. Allied forces were preparing for the Battle of Normandy which would liberate western Europe. The mystery-thriller film ‘Gaslight’ starring Charles Boyer and Ingrid Bergman had premiered in New York and in Woking, the composer of ‘The March of the Women’ anthem of the women’s suffrage movement, Ethel Smyth, died aged 86. Bereavement and loss were everywhere and Spiritualism again became a way (it had first gained popularity after the First World War) for people to find comfort and solace.

In a barely lit room in Romford Road, Forest Gate, 72-year-old Jane Rebecca Yorke had fallen into a trance. She began to communicate with her spirit guide or ‘communicant’, in her case a Zulu. She had also claimed to have received messages from Queen Victoria and Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, creator of Sherlock Holmes and vocal supporter of Spiritualism. The hushed room of mainly women listened to the messages she conveyed. Constance Lerner was told of how her dead baby was beside her, holding a bunch of roses. William Watt was informed that his father had perished in World War One and William Holliwell, that his brother had burned to death on a bombing mission.

What Yorke’s spirit guide hadn’t told her was that these three were undercover police officers sent to investigate her after complaints from the public. Yorke was arrested and, on the 11th July, was charged with;

‘Conspiring together with persons unknown to pretend to exercise, or use, a kind of conjuration (magic spell) and that through the agency of Mrs. Yorke, spirits of deceased persons appeared, and that the spirits were communicating with living persons present’

‘Why after 23 years?’ Yorke asked officers. ‘I have got to say that I am a born medium’.

The case had attracted a lot of attention and the local newspaper, the Stratford Express, ran an eight-page piece on Yorke. On the advice of the Director of Public Prosecutions, Yorke was remanded for trial at the Central Criminal Court (Old Bailey) in September. She was found guilty on all seven counts and fined £5 and bound over to keep the peace for three years. The relative leniency of the punishment was put down to her age, disability and previous good character. It was an anti-climactic end to what had been a sensationalised case. There are no photos of Yorke and not much is known about her after the case. It is thought she died in Hackney, sometime in the early 1950s.

Most of Yorke’s paying customers were vulnerable and desperate women who had lost husbands and sons in the war and were seeking a way to communicate with their lost loved ones, and while nobody had ever accused Yorke of being a witch, the Witchcraft Act 1735 was the only piece of legislation available for arresting and charging her for her crimes.

In the wake of the verdict, some Spiritualist meetings were banned, giving the findings of the court as the reason. While there had undoubtedly been some fraudulent mediums, Spiritualists felt that they were being unfairly targeted and that the laws in place were not fit for the 20th century. This led to the 1951 Fraudulent Mediums Act. This law prohibited a person from claiming to be a psychic, medium or other spiritualists while attempting to deceive or make money from the deception.

The 1951 act was replaced in 2008 by the Consumer Protection from Unfair Trading Regulations. The law that had seen an innocent Joan Peterson hanged as a witch in 1652 and Rebecca Yorke fined £5 in 1944 for preying on grief-stricken women, would eventually result in a double-glazing company being the first to fall foul of the new laws. I wonder if Jane Rebecca Yorke could have predicted that?

Sources:

The Malleus Maleficarum – Selected, translated and annotated by P.G Maxwell-Stuart, Manchester University Press ISBN 978-0-7190-6443-2

E7 Now & Then: Forest Gate’s Unique Place in the History of Witchcraft, http://www.e7-nowandthen.org/2016/03/forest-gates-unique-place-in-history-of.html

Executed Today: 1652 - Joan Peterson, https://www.executedtoday.com/2012/04/12/1652-joan-peterson-the-witch-of-wapping/

Frames for Murder: The Witch of Wapping, http://winsham.blogspot.com/2015/08/witchcraft-or-conspiracy-witch-of.html

Witch of Wapping pamphlet – Winshamblogspot.com

Rebecca Jane Yorke – Newspaper article from Stratford Express 14th July 1944.

Author

Written by Alison Murray.